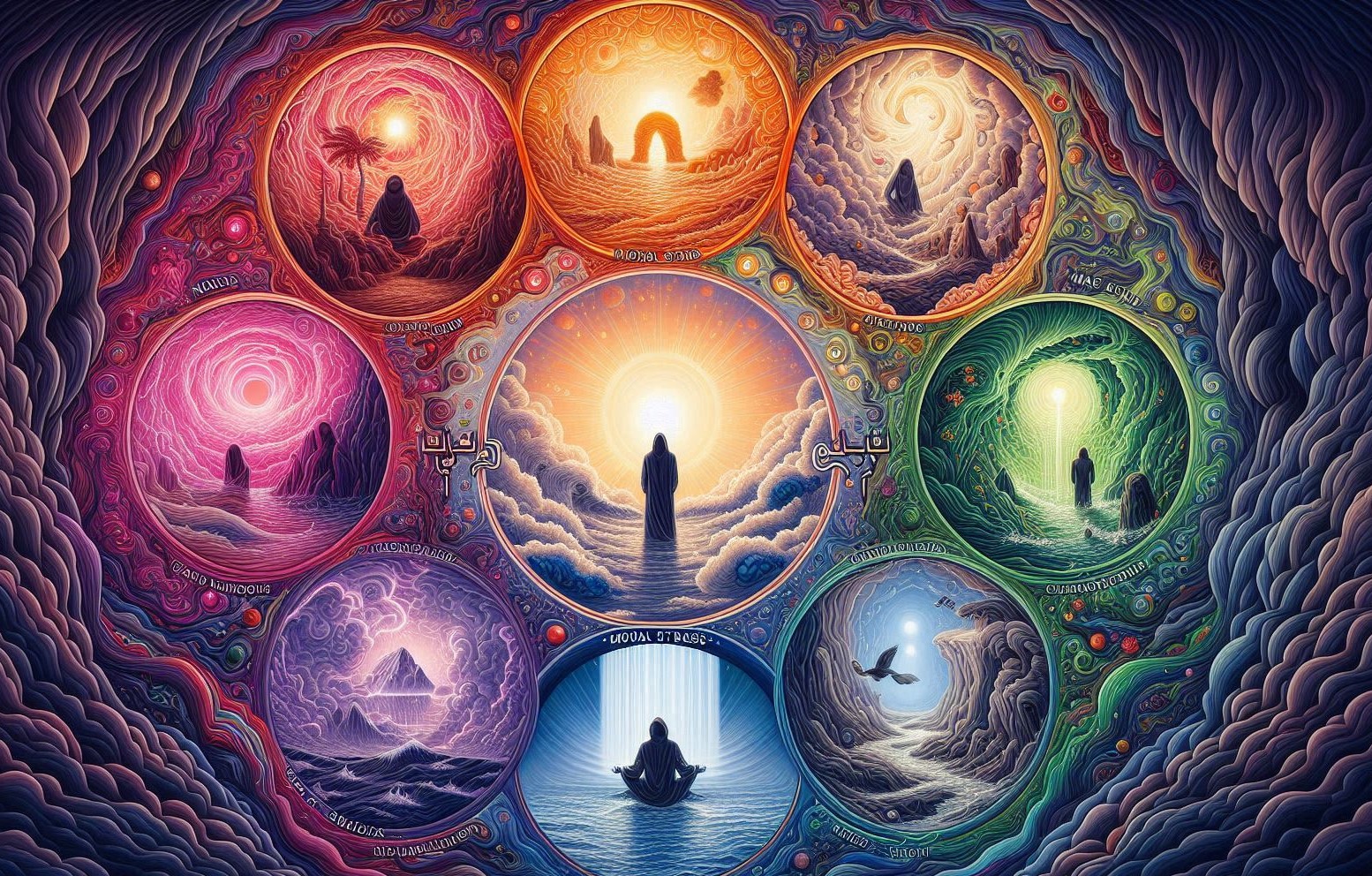

The Landscape of the Inner Self

Within the Islamic spiritual and psychological tradition, the concept of the nafs (often translated as the self, psyche, or soul) represents one of the most profound frameworks for understanding human consciousness, moral development, and psychological well-being. Unlike reductive materialist psychology, the Islamic paradigm views the human being as a multi-layered entity comprising the nafs (the appetitive self), the qalb (the spiritual heart or center of cognition and faith), the ‘aql (the intellect), and the rūḥ (the transcendent spirit). The journey of the nafs is a central theme in Islamic spirituality, detailing a path of purification (tazkiyah) from a state of primal disobedience to one of serene contentment.

This guide will explore in detail the seven primary stages of the nafs as delineated in classical Islamic texts, primarily drawing from the Qur’ān and the exegetical and Sufi traditions. Critically, it will examine each stage not only as a spiritual station but also as a distinct psycho-emotional and stress state. By mapping these traditional categories onto modern understandings of stress, anxiety, and well-being, we can appreciate the nafs model as a dynamic, holistic psychology. The journey begins with the tumultuous nafs al-ammārah and culminates in the tranquil nafs al-mutma’innah, providing a complete roadmap for human transformation.

Nafs al-Ammārah (The Commanding Self) and the State of Chaotic Stress

Nafs al-ammārah is the basest level of the self, driven almost entirely by primal impulses, desires, and passions. The term originates from the Qur’ān: “Indeed, the nafs is a persistent enjoiner of evil” (Qur’ān 12:53). At this stage, the individual is in a state of internal chaos, where the lower impulses command the intellect and the heart. The primary drivers are instant gratification: hunger, lust, anger, greed, and envy.

Corresponding Stress State: Chaotic and Acute Stress

The psychological state of nafs al-ammārah is characterized by high-arousal, chaotic stress. This is akin to a perpetual “fight-or-flight” response, but one triggered by internal cravings and frustrations rather than external threats. The individual experiences:

- Impulsive Reactivity: Actions are immediate reactions to stimuli, leading to poor decision-making and regret.

- Internal Conflict: While the nafs commands, the innate human conscience (fiṭrah) or intellect may protest, creating a state of cognitive dissonance and guilt, which further fuels stress.

- Anxiety of Deprivation: There is a pervasive fear of not obtaining what is desired, leading to restless anxiety.

- Short-Term Gratification Cycles: Stress is temporarily alleviated through indulgent acts, only to return more intensely, creating an addictive cycle.

This stage represents a profound lack of self-regulation. Modern psychology might identify this with high neuroticism, poor impulse control, and conditions like intermittent explosive disorder or addictive behaviors. The stress is disordered, externalized (often blaming others), and deeply corrosive to long-term mental health.

Nafs al-Lawwāmah (The Self-Reproaching Self) and the State of Moral Stress

The nafs al-lawwāmah marks the beginning of spiritual awakening. It is the conscience-stricken self that regrets its wrongdoings. The Qur’ān attests to this state: “And I swear by the blaming soul [nafs al-lawwāmah]” (Qur’ān 75:2). This nafs is in a state of civil war—it still falls into error but possesses enough awareness to recognize its failings and engage in self-criticism.

Corresponding Stress State: Moral and Acute Stress

The stress here evolves from chaotic to moral. It is the anxiety and anguish born of conscience.

- Guilt and Shame: The primary stressors are internalized feelings of guilt (“I did a bad thing”) and shame (“I am bad”). This creates a persistent, ruminative stress state.

- Cognitive Dissonance: The gap between one’s actions and one’s understanding of right and wrong creates significant psychological tension.

- Motivational Conflict: The nafs still pulls toward desire, while the awakening qalb pulls toward virtue. This internal tug-of-war is exhausting and stressful.

- The Stress of Accountability: There is a dawning awareness of being accountable for one’s actions, which can be a source of existential anxiety.

While painful, this stress is productive and transformative. It is the engine of repentance (tawbah). In modern terms, this aligns with the concept of moral injury and the psychological distress that accompanies a violation of one’s own ethical code. It is a necessary suffering that propels the seeker toward change and seeking help, whether through spiritual counsel or therapeutic intervention.

Nafs al-Mulhamah (The Inspired Self) and the State of Striving Stress

Nafs al-mulhamah is the stage where the self begins to receive inspiration (ilhām) to choose good over evil. It is the self that is actively engaged in the struggle (jihād al-akbar, the greater struggle) and is being guided. While not explicitly named in the Qur’ān, scholars derive it from the verse: “And [by] the soul and He who proportioned it. And inspired it [alhamaha] with its wickedness and its righteousness” (Qur’ān 91:7-8). At this stage, the individual is actively practicing spiritual disciplines: prayer, fasting, charity, and remembrance (dhikr), and is beginning to experience glimpses of peace and inspiration.

Corresponding Stress State: Eustress of Striving

The stress state here shifts from destructive to constructive. This is primarily eustress—the positive stress of growth, challenge, and pursuit of meaningful goals.

- Disciplined Effort: Stress comes from the exertion of maintaining new habits, resisting ingrained temptations, and the physical/mental effort of sustained worship and good deeds.

- The Stress of Vigilance: Constant self-examination (murāqabah) is required to maintain progress, which can be mentally taxing.

- Intermittent Doubt and Elation: The journey is not linear. Setbacks can cause temporary returns to the stress of lawwāmah, while moments of success and spiritual inspiration bring relief and joy, creating an oscillating but overall upward-trending emotional state.

- Social Stress: Embarking on a path of piety can create friction with one’s previous social circles or lifestyle, leading to relational stress.

This stage is analogous to the stress experienced by an athlete in training or a student mastering a difficult subject. It is tiring but fulfilling. The individual has moved from being a passive victim of their nafs to an active participant in its reformation.

Nafs al-Mutma’innah (The Contented Self) and the State of Tranquility

This is the stage of profound peace and arrival. It is the self that is fully at rest and content with God. The Qur’ān addresses this soul directly: “O contented soul [nafs al-mutma’innah]! Return to your Lord, well-pleased and pleasing [to Him]. Enter among My [righteous] servants. And enter My Paradise” (Qur’ān 89:27-30). This nafs has achieved a stable state of inner peace through sincere devotion, remembrance of God (dhikr), and submission (islām).

Corresponding Stress State: Homeostasis and Resilience

The corresponding state is one of tranquility, homeostasis, and profound resilience.

- Stress Response Regulation: The individual is not immune to life’s external stressors (loss, illness, hardship), but their baseline state is one of calm. The physiological stress response (cortisol, adrenaline) is well-modulated and not easily triggered by trivial matters.

- Cognitive Reappraisal: Challenges are reframed through a lens of faith—as tests, opportunities for growth, or divine decree (qadr) to be accepted with patience (ṣabr). This dramatically reduces the perception of threat.

- Emotional Stability: There is a freedom from the tyranny of impulsive desires and the torment of a guilty conscience. Joy (surūr) and contentment (riḍā) become dominant emotional states.

- Secure Attachment: The ultimate source of stress reduction is the soul’s secure attachment to God, leading to feelings of being cared for, protected, and guided. This mirrors the psychological concept of a secure base enabling exploration and resilience.

In modern psychological terms, this aligns with the highest levels of emotional regulation, mindfulness, and well-being. It correlates with low levels of anxiety and depression, high heart rate variability (indicative of autonomic nervous system balance), and a sense of purpose and meaning in life.

Nafs al-Rāḍiyyah (The Pleased Self) and the State of Acceptance

Following contentment is a stage of active pleasure and satisfaction. Nafs al-rāḍiyyah is pleased with whatever decree (qaḍā) God has ordained. It does not merely tolerate circumstances but finds genuine pleasure in God’s will, believing it to be the ultimate good. This is a more active form of contentment.

Corresponding Stress State: Existential Ease

The stress state here is characterized by the near-elimination of existential and psychological stress.

- Eradication of Resentment: Stress often arises from resistance to reality (“why me?”). This nafs has dissolved that resistance entirely.

- Proactive Acceptance: Even in difficulty, the individual seeks and finds the wisdom or potential blessing, transforming potential distress into a state of curious or grateful engagement with life’s tests.

- Flow State Alignment: The individual’s will is so aligned with their perception of divine will that actions feel fluid and free of internal conflict. This reduces the stress associated with decision-making and doubt.

This stage represents the pinnacle of stress inoculation. The individual has developed such robust cognitive and spiritual frameworks that most of life’s events are processed without triggering a significant stress response.

Nafs al-Marḍiyyah (The Pleasing Self) and the State of Symbiotic Harmony

This is a reciprocal stage: just as the soul is pleased with God, it becomes pleasing to God. Its actions, intentions, and very being are in harmony with divine pleasure. The focus shifts entirely from the self’s satisfaction to becoming a vessel for divine attributes—showing mercy, justice, and beauty in the world.

Corresponding Stress State: Purpose-Driven Engagement

Stress in this stage is almost entirely sublimated into purposeful action.

- Stress as Fuel for Service: Any distress witnessed in the world (injustice, poverty, ignorance) becomes a motivator for compassionate action, not a source of personal despair.

- Absence of Ego-Stress: Since the ego (anāniyyah) is diminished, stresses related to personal reputation, insult, or failure are minimal. The individual is “thick-skinned” in the face of personal criticism but “thin-skinned” in the face of others’ suffering.

- Sustained Energy: The alignment with a transcendent purpose provides a continuous source of energy and buffers against burnout, a common modern stressor.

This stage mirrors the psychological concept of “self-transcendence” and altruistic behavior, which are strongly linked to longevity and life satisfaction.

Nafs al-Ṣāfiyyah / Kāmilah (The Purified/Complete Self) and the State of Unitive Consciousness

The final stage is that of complete purification and perfection. The nafs is now like a clear mirror, utterly purified of dross, reflecting the divine qualities. It has returned to its primordial, innocent nature (fiṭrah), but at the level of conscious perfection. This is the stage of the prophets and the most perfected saints (awliyā).

Corresponding Stress State: Transcendent Peace

This represents a transcendent state beyond conventional understanding of stress and coping.

- Unitive Perception: The illusion of separation—a primary source of existential anxiety—is dissolved. The individual experiences creation as interconnected and emanating from the Divine.

- Spiritual Abiding: A permanent state of inner peace and communion, often described as “abiding in the Divine Presence.” This is the ultimate anti-dote to stress, which is fundamentally a perception of threat to a separate self.

- Effortless Being: Virtue and right action flow spontaneously from this purified state without internal struggle, eliminating the striving stress of earlier stages.

While this state may be rare, it represents the ultimate goal: a human psyche so completely integrated and aligned that it exists in a sustained state of flourishing, acting as a conduit for peace in the world.

Conclusion

The seven stages of the nafs provide a sophisticated, non-linear map of human psycho-spiritual development. Crucially, each stage encapsulates a distinct stress phenotype—from the chaotic stress of addiction and impulse to the eustress of growth, and finally to the transcendent resilience of unitive consciousness. This framework does not pathologize normal human struggle but contextualizes it as part of a necessary journey.

For contemporary mental health practice, this model offers invaluable insights. It suggests that true well-being (mutma’innah) is not merely the absence of mental illness (the DSM model) but the presence of a positive, integrated state achieved through moral struggle, self-awareness, and the cultivation of meaning and connection to the transcendent. Therapeutic techniques like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which aim to correct distorted thinking, find a deep resonance with the work of nafs al-lawwāmah and mulhamah. Mindfulness and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) echo the present-moment awareness and detached observation cultivated in mutma’innah.

Ultimately, the journey of the nafs is a journey from fragmentation to integration, from slavery to passion to mastery of the self, and from debilitating distress to unshakable peace. It remains a timeless paradigm, offering not just a diagnosis of the human condition but a detailed prescription for its healing and ultimate fulfillment.

SOURCES

Al-Ghazālī, A. H. M. (ca. 1107/1997). The Alchemy of Happiness (C. Field, Trans.). (Original work published in the 12th century).

Chittick, W. C. (2000). Sufism: A Beginner’s Guide. Oneworld Publications.

Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyya. (ca. 1350/2003). The Spiritual Disease and Its Cure (M. A. Qureshi, Trans.). Ta-Ha Publishers. (Original work published in the 14th century).

Ibn ‘Arabī, M. i. A. (ca. 1240/1980). The Bezels of Wisdom (R. W. J. Austin, Trans.). Paulist Press. (Original work published in the 13th century).

The Noble Qur’ān. (English translation of meanings). (Various translators). (Original revelation circa 610–632 CE). [Verses cited: 12:53; 75:2; 91:7-8; 89:27-30].

Lumbard, J. E. B. (Ed.). (2015). The Study of Sufism: Orientalists and Mystics. Routledge.

Helminski, K. (1992). Living Presence: A Sufi Way to Mindfulness and the Essential Self. TarcherPerigee.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904.

HISTORY

Current Version

Dec 23, 2025

Written By:

SUMMIYAH MAHMOOD